Athletes as Investors and Entrepreneurs

In 1905 baseball bat maker J.F. Hillerich & Son paid player Honus Wagner an undislosed sum for the right to use a facsimile of his signature on “the Louisville Slugger,” marking the beginning of the lucrative practice of athletes supplementing their income through marketing.

Today, in basketball (the American sport that allows for the most lucrative endorsement deals), the top 10 endorsement deals are worth some $260 million. LeBron James of the Los Angeles Lakers, the top-earning U.S. athlete in endorsements, makes more than double his $31.4 million salary thanks to deals with AT&T, Beats, Nike, Walmart, Rimowa, GMC and Blaze Pizza.

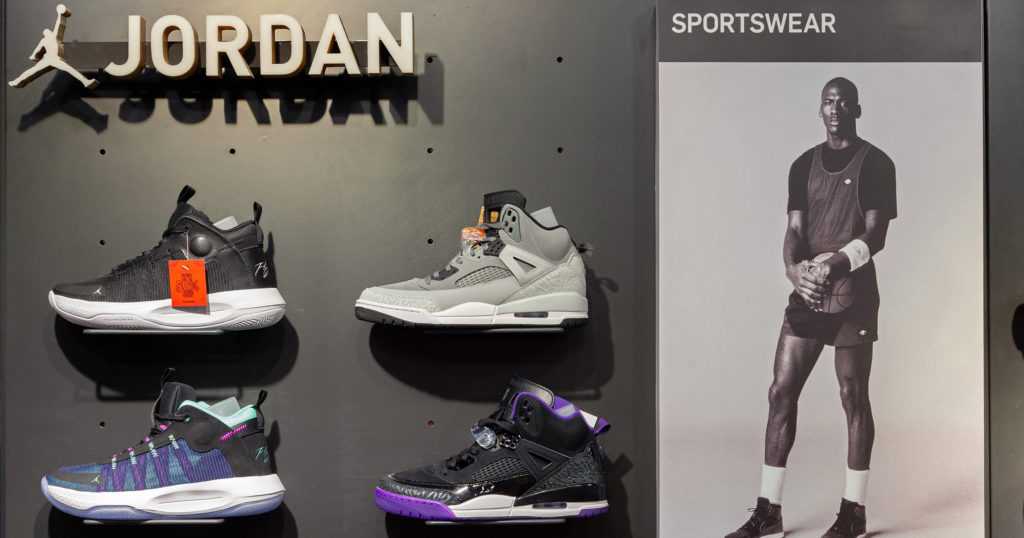

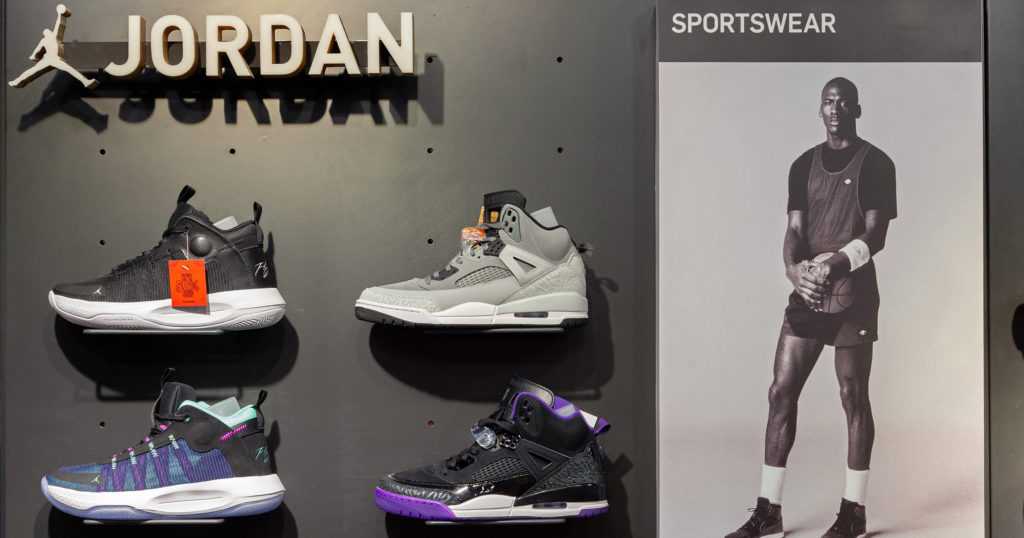

Of course, the $64 million James earns from endorsements, while impressive, pales in comparison to the money that licensing and endorsements has brought in for former Chicago Bull Michael Jordan. Licensing, like endorsements, are a marketing arrangement. Where with endorsements a celebrity promotes the use of a product or service, licensing involves the leasing of a specific thing, such as a likeness, logo, name, or slogan.

Jordan – like James, considered one of the greatest basketball players of all time – doesn’t even make the top 10 for lifetime earnings from the sport itself. Most of his $2 billion-plus fortune comes from his off-court ventures. “His Airness” draws a 5% royalty from every Air Jordan shoe sold by Nike. His brand generates more than $3.1 billion in a year for the company. And it’s just one of many deals that Jordan has struck. Other companies who have paid for the privilege of being associated with Jordan include McDonald’s, Chevrolet, Gatorade, and Wheaties, to name only a few.

HALO EFFECT

Both endorsements and licensing presume a “halo effect” from the athlete’s fame and achievement. Nobody expected to run into Michael Jordan at his now-closed steakhouse in New York City’s Grand Central Terminal, but the use of his name lent a cachet to what might have been an otherwise non-distinctive restaurant. Wearing Air Jordans won’t turn an average amateur athlete into a star player, but they let fans express their affinity and admiration.

Such arrangements have long been easy – albeit sometimes puzzling – money for athletes. Why was Yankee Clipper Joe DiMaggio plugging coffee makers in his later years – or a savings bank? What’s the connection between former race-car driver Danica Patrick and website company GoDaddy? Yet it’s hard to find fault with highly paid athletes looking to supplement their incomes. Professional athletes know that their careers will only last so long and can be cut short by injury, and this unique form of entrepreneurship allows forward-thinking athletes to leverage their celebrity into a second, often more lucrative income stream.

Many athletes are now using their combination of clout and cash to invest not just in their own futures, but in new technologies and nascent businesses, fledgling entrepreneurs, underserved communities, and ventures far afield from their athletic accomplishments. Here is a look at how some athletes – some still active; others retired – are investing and acting as entrepreneurs.

MAGIC JOHNSON

Any list of athlete-entrepreneurs would have to include former Los Angeles Laker Magic Johnson, who at one point was the highest-paid player in the National Basketball Association. He was also one of the first athletes to carve out a successful career in business. After retiring from playing in 1992 (he returned to the game briefly, for the ’95-’96 season), he turned to a variety of ventures. His post-basketball life including a stint as a talk-show host, a foray into the music business, ownership of a nationwide chain of theaters, and a partnership with Starbucks that helped introduce the coffee chain into minority neighborhoods.

LEBRON JAMES

“King James” has a lucrative and impressive career in Hollywood going for him. He played himself in the 2015 movie Trainwreck, which may not seem like a stretch until you realize that he improvised much of his dialogue. He also appeared in the movies Space Jam, and Smallfoot, and has produced numerous projects, including the award-winning Self-Made, a Netflix series inspired by the life of Madame C.J. Walker.

KYLE LOWRY

The 35-year-old Toronto Raptors guard is one of a growing group of basketball players looking to make an impact in the technology industry. He has said his goal is to “build generational wealth and break down systemic barriers,” referring to the relatively low numbers of Black participants – whether as investors or founders – in Silicon Valley. “Getting the African-American, the Black person into those types of positions, it changes the outlook of the culture, right?” Lowry said. “It changes the thought processes of who these people are.”

KEVIN DURANT

The New York Nets forward is one of the founders, along with his manager Rich Kleiman, of Thirty Five Ventures, which has invested in more than 75 companies in such areas as health and wellness, cryptocurrency, media, and fintech. Durant’s company is known for having strong relationships with both venture capital and private equity firms. Among his investments was an early stake in food-delivery service Postmates.

JUNIOR BRIDGEMAN

The former NBA player used the off-seasons of his 12-year career to study business, initially focusing on fast-food franchises. He eventually owned more than 100 Wendy’s and Chili’s restaurants before selling them in 2016. In 2020, he bought the bankrupt Ebony and Jet magazines. He described his goal of turning the iconic chroniclers of Black life and culture as “a labor of love.” Both magazines have robust online presences since the acquisition by Johnson.

SERENA WILLIAMS

In 2014, the tennis great founded Serena Ventures, to invest “in companies that embrace diverse leadership, individual empowerment, creativity and opportunity.” The female-led company has invested in more than 50 companies with a combined market cap of $14 billion. Among the companies in Serena Ventures’ portfolio: Impossible Foods, online education company Master Class, women’s razor startup Billie, and weight-loss company Noom. She also has started her own clothing and jewerly lines, S by Serena Williams, Serena Williams Jewelry.

MARIA SHARAPOVA

Selling sweets doesn’t seem like an obvious fit for a former star athlete. But retired tennis player Maria Sharapova says that starting as a child, she would look forward to some kind of treat after practice, which was often some kind of candy. In fact, the message that comes with a box of her Sugarpova candy says, “Thank you for treating yourself!” She founded the company in 2013, when a shoulder injury led her to think about her career beyond tennis. While she has received criticism for promoting what some consider “unhealthy food,” she says that moderation, not deprivation, is a key to health.

ALEX RODRIGUEZ

“When people think about my career, they think about the championships, the RBIs, the home runs, but what they don’t realize is that I’m fifth all-time in striking out, so that means I have a Ph.D. in failing,” Rodriguez once told Hispanic Network Magazine. “But I also have a master’s in getting back up, and that’s what America is all about: getting back up, not getting defined by your mistakes.” Rodriguez, at one time the highest-paid player in Major League Baseball, started investing in real estate in 2003, well before his retirement in 2016. His latest business venture: a concealer stick for men, for the “Hims” brand of wellness products. Rodriguez is not only an investor; he is featured in ads for the “Blur Stick.”

CRISTIE KERR

For golfer Cristie Kerr, her boutique, California-based winery is no vanity project. Kerr Cellars, started in 2012, grew out of her love for California wines, which began after visiting several Napa wineries in 2000. In 2006, she launched Curvature wines to help raise money for breast cancer research in honor of her mother, who was diagnosed with the disease in 2003. In 2015, she and husband Erik Stevens debuted their first three wines from Kerr Cellars. The vintage was 2013; the same year she passed the Court of Master Sommeliers level 1 test. She still supports breast cancer research through the Curvature label.