Bacon, Eggs, and Public Relations: How PR Pioneer Edward L. Bernays Changed America

If you think of bacon and eggs as a great breakfast, cigarettes as an equal opportunity vice, and beer as a beverage for the moderate drinker, you have Edward L. Bernays to thank.

Often touted as the father of public relations, Bernays transformed what had been an unsophisticated matter of attracting attention into sophisticated, multi-level campaigns that could mold and manage public opinion.

Born in Vienna in 1891 and raised in New York, Bernays had his first success as a theatrical publicist, making stars of the great Italian tenor Enrico Caruso and the avant-garde Ballet Russe.

But World War I changed the course of Bernays’ career. During the war years, Bernays served on the Committee on Public Information, an innovative government propaganda service that whipped public opinion into supporting American intervention in the European war through speeches, posters, newspapers, and film – the then-new mass media.

“When I got back from the war, I realized that ideas could be as important weapons as anything,” he recalled in a 1986 interview conducted by a researcher for Ball State University in Muncie, Ind. He decided to apply what he had learned about running publicity campaigns for the Committee on Public Information in the service of corporate clients.

Further influencing Bernays’ approach to the malleability of public opinion was his famous uncle, Sigmund Freud. After the war, Bernays’ reading of the preeminent psychiatrist’s work and ongoing correspondence with Freud led Bernays to see an opportunity to strengthen the effectiveness of publicity campaigns by appealing to both the public’s conscious and unconscious desires.

A new profession

Going into business in New York as a new kind of professional public-opinion manager he called “counselor of public relations” and vying with Ivy Lee as the founder of a new profession, Bernays executed a number of campaigns in the 1920s that played an important role in changing American society.

Bernays’ trademark strategies often involved roundabout ways of meeting his client’s goals. As his biographer Larry Tye put it in The Father of Spin (published in 1998), “Hired to sell a product or service, he instead sold whole new ways of behaving, which appeared obscure but over time reaped huge rewards for his clients and redefined the very texture of American life.”

For example, when Beech-Nut Packing Company, the country’s biggest bacon producer, found its sales were falling off, the company called Bernays. In the 19th century, when more work required manual labor, enormous breakfasts were the rule: bacon and eggs, doughnuts, pie, and coffee. By the 1920s, however, less demanding work and the desire to stay slim had led people to cut their breakfast down to a piece of toast, orange juice, and a cup of coffee.

Bernays hired a well-known New York physician to ask doctors all over the country whether a light breakfast or a heavy breakfast was better. The doctors confirmed, in Bernays’ words, that a heavy breakfast was “scientifically desirable.” Six months after he publicized the survey’s results, Beech-Nut’s sales boomed, and a classic breakfast was reborn.

Smoking too became much more popular through Bernays’ work to promote Lucky Strike cigarettes. Until the late 1920s, relatively few women smoked, and George Washington Hill, CEO of the American Tobacco Company, wanted to change that. He hired Bernays to help him promote his slogan “Reach for a Lucky instead of a sweet.”

Here too, Bernays took an oblique route, first encouraging the popularization of pictures of models in clothing that emphasized slenderness, then promoting Paris fashion houses that photographed thin models, and finally, publicizing a study about the negative effects of excess sugar on the human body.

But this only made it permissible for women to smoke at home; not in public. A. A. Brill, a well-known psychoanalyst, told Bernays that the public saw cigarettes as “torches of freedom” – both a symbol of masculinity and a male prerogative. To combat “the silly prejudice” against women smoking on the sidewalk, Bernays had his secretary invite 30 debutantes to a demonstration on Fifth Avenue during the 1929 Easter Parade. Ten women showed up for the “Torches of Freedom” demonstration, attracting press coverage from all over the country, and setting the stage to change another social norm.

Bernays also helped shape modern attitudes toward beer. After Prohibition ended in 1933, many localities voted to stay dry. Brewers wanted to make sure that the public never banned alcohol – or at least beer – again. Under Bernays’ direction, brewers sponsored the development of a test that police could use to measure the alcohol level in a driver’s blood, encouraged shutting down places that served under-age drinkers, ran advertisements emphasizing moderation and opposition to hard liquor, and even described beer drinking as “a vaccination against intemperance.”

A not-so-mad man

Perhaps the biggest contribution Bernays made to modern life, however, was the promotion of public relations itself. His idea was to take what had been seen as relatively unserious work (a reporter once disparaged Bernays as “the Baron of Ballyhoo”) and reinvent publicity as a sophisticated, complex profession, which he outlined in several books and a newsletter sent regularly to many major companies.

But his work in developing more sophisticated techniques of persuasion had a serious downside: Fascists in Germany and Spain paid close attention to American advertising generally and Bernays’ work specifically. In the early 1930s, a reporter told Bernays he saw Bernays’s book Crystallizing Public Opinion on the bookshelf of Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s propaganda minister.

Bernays didn’t regret his work. He said any tool could be used for good or bad purposes. “We worked out the engineering of consent, which applies to any social goal,” he explained in the 1986 Ball State interview. “But the people who don’t have social goals, unfortunately, can also employ it.”

However, despite his reputation as a Svengali of opinion, Bernays believed there were limits to what public relations practitioners could accomplish. “People blame Eddie for almost every ill in modern society, and I think that is probably excessive,” said Lucas Bernays Held, director of communications for the Wallace Foundation in New York and a grandson of Bernays. “One of the things Eddie would always repeat – and this has stuck in my mind … was that actions speak louder than words.”

According to Held, Bernays saw the public relations professionals’ role not only as being an external advocate for an organization but an internal advocate who encourages the pursuit of responsible policies. “Arguably, if public relations were more attentive to his idea of a two-way street, the field’s reputation would be better,” noted Held.

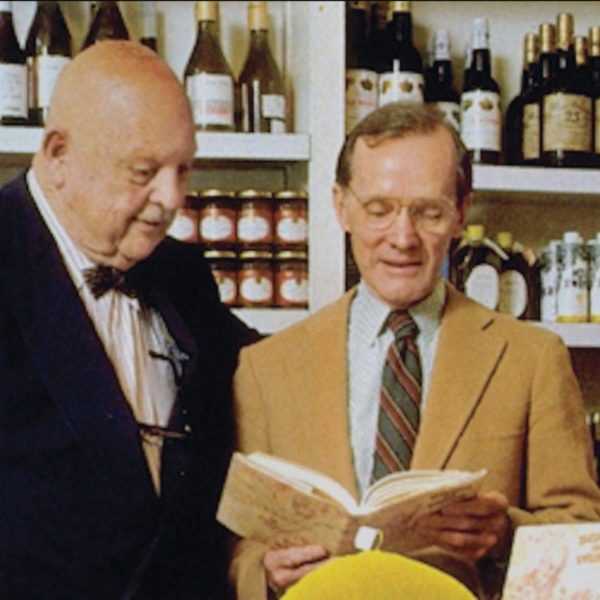

Professionally, he continued to work well into his 70s, doing pro bono work for the American Cancer Society and other organizations, advising students on job searches (one gambit he recommended was reaching out to industry luminaries on the pretext of writing a study on their field), and tending to his own legacy as the Father of Public Relations.

Although Bernays was aided by outliving other contenders to the title by – he died in 1995 at 103 – industry leaders acknowledge that he made an outsized contribution. As Harold Burson, co-founder of global public relations giant Burson-Marsteller, put it in Tye’s biography, “We’re still singing off the hymn book that he gave us.”