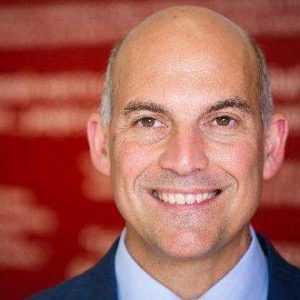

The Walmart Effect

Matthew A. Waller, dean of the Walton School of Business, writes about capitalism’s potential to alter the status quo of an industry, as Walmart did with retailing. Just as important is capitalism’s effect on the communities where companies operate; creating jobs, opportunity, and wealth.

There is no greater example of capitalism in America than Sam Walton, founder of Walmart. He was a true visionary whose revolutionary approach to collaborating with suppliers transformed not only the retail industry but Northwest Arkansas.

In his never-ending quest for improving his business, Sam Walton did something no one had ever thought to do: In the 1980s, he started sharing key data with his suppliers: point of sale data, sales by SKU, inventory data, and pricing information. Suppliers were shocked, because this was information that could be used to the suppliers’ advantage against both their competitors and the retailer. But Sam saw the possibilities in partnering with suppliers rather than the threat.

Imagine that you’re P&G and you’re working with Walmart and using all of that data around a product like Pampers. Yet there’s Kimberly Clark, whose Huggies compete directly with Pampers. Well, you both end up sending your best and brightest to Bentonville — your smartest analysts, strategists, and marketing people — so you can compete more effectively. In 1988-’89 P&G sent some of their people, and then they started moving whole teams here. As of 1994, there were only a handful of supplier teams in the area.

Thanks to Walmart, Bentonville itself now has a population of more than 40,000 and is still growing.

Other suppliers also recognized possibilities and the benefits that accrue to both sides, and moved teams to Bentonville and the surrounding towns. By 2011 there were 9,000 people in Northwest Arkansas just collaborating with Walmart. That doesn’t include all the other people who moved here, such as those people’s families. In 1950, Bentonville had only 3,000 residents; Northwest Arkansas was reliant on agriculture and poultry. Thanks to Walmart, Bentonville itself now has a population of more than 40,000 and is still growing. The region itself has some 550,000 residents and is an innovation hub bookended by Bentonville and Fayetteville, home of the state’s flagship university.

The Transformation of Northwest Arkansas

Fayetteville, Arkansas

Did you know Northwestern Arkansas is in the midst of an economic boom? With more Fortune 500 companies per capita than any other part of the country, the region has seen growth across industries, including business, arts, outdoor recreation and education.

Walmart

With Walmart’s headquarters in Benton County, more and more consumer products and food suppliers are bringing jobs to the area to meet the needs of the major retailer’s supply chain. But the traditional local businesses aren’t the only ones impacting the area’s footprint.

Fayetteville Business

Northwest Arkansas was ranked No. 3 among places to found a startup, following Silicon Valley and New York City, leading to Benton County’s population doubling since 2000.

Crystal Bridges Museum

Northwestern Arkansas is also home to an increasingly robust collection of arts and culture exhibits. The Walton Arts Center in Fayetteville is visited by nearly half of the area’s residents yearly and The Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art welcomed over 600,000 visitors in 2015. In 2015, the nonprofit arts and culture industry in Northwest Arkansas generated an estimated $131 million in economic activity, and supported nearly 5,000 jobs.

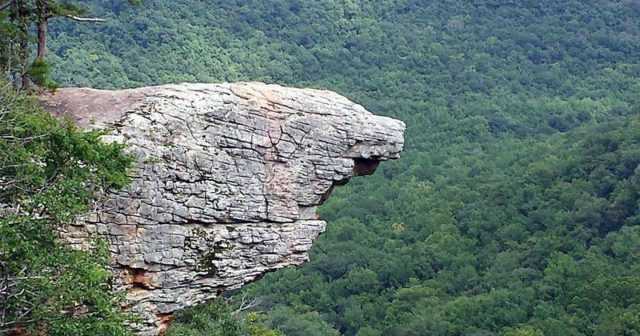

Whitaker Point Trail

In addition, the area is home to an extensive trail system for both hiking and cycling. Over the past 7 years, 200+ miles of new hard and soft-surface trails have been installed, drawing a large portion of the area’s residents. In 2015, over two thirds of Northwest Arkansas residents visited and utilized the trails at least once throughout the year.

Univ. of Arkansas, Old Main

As the regional home of the Razorbacks, education remains a pillar of Northwest Arkansas success, as well. The University of Arkansas enrolls over 27,000 students across more than 200 academic programs, and the Sam M. Walton College of Business is among the top public business programs in the country, ranked 26th on the 2017 U.S. News & World Report of “America’s Best Colleges.” Capable of seating over 70,000 passionate fans, the Donald W. Reynolds Stadium is home to U of A’s Razorbacks.

NW Arkansas Landscape

As the area continues to grow, quality of life of residents is on the rise, and we can’t wait to see what innovations develop out of Northwest Arkansas next.

Growth has also come from the other businesses that either became part of the greater Walmart ecosystem or are complementary businesses, such as transportation company JB Hunt, and Tyson Foods. The expertise that is here because of Walmart’s impact helps all of these companies.

We’re now seeing a second wave of growth with the technology companies that have located here to work with the companies that sell to Walmart. We’re developing a culture of innovation in consumer goods, which is spurring startups like Field Agent, which supplies analysis to the supplier teams. That company, which is headquartered in Northwest Arkansas, didn’t even exist five years ago. That’s how great Walmart’s effect on the area has been.

But the effect extends beyond business and the retail industry. The quality of life is higher than it was even 10 years ago. You see it in the restaurants, cultural attractions like Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, the new culinary institution, Brightwater, and a world-class K-12 private school, the Thaden School. These anchors help attract people from all over the country who see the potential for a good career, superior schools for their children, and a high standard of living. U.S. World and News Report named Fayetteville one of the best places to live in the country, ranking it No. 5.

The region was also named the No. 3 place to found a startup (outside of Silicon Valley and New York City), trailing only Cambridge, MA, and Santa Monica, CA, by CRM orchestration company DataFox. In fact, the only thing holding back innovation in Arkansas is the supply of managerial talent, and we’re doing our best to help solve that problem.

The Walton School of Business is now a net importer of talent for Arkansas. We have an 88% placement rate at graduation, and we’re attracting higher-caliber students and more of them. In the last two years, the number of degrees we award from the business school increased by 40%.

Walmart’s success has forced other retailers to become more efficient and that’s part of what happens with capitalism: It forces everyone to be more competitive.

There’s always been this perception that Walmart is a tough negotiator. Walmart didn’t get cost-savings through tough negotiations. They got them through innovative approaches, like data-sharing, logistics and collaboration. All of that was driven by the desire to win market share. Walmart’s not a tough negotiator — they’re a tough competitor.

Walmart’s success has forced other retailers to become more efficient and that’s part of what happens with capitalism: It forces everyone to be more competitive — with pricing, with service, with efficiency. That’s good for the companies and it’s good for the customers. And it’s been awfully good to — and for — Northwest Arkansas. Sam’s decision and suppliers’ response spurred the change that transformed Northwest Arkansas into the innovation hub it is today.